For Leonard Cohen

I wanted to, for the birthday of Leonard Cohen, on this, the last day of summer, write something very fast and to the point about this odd man who I’ve looked to so much over the years in both parasocial and creative ways. Here’s to the complicated relationship humans like to have with people we will never know. I’d say there’s something of the theological and monarchical in it, but that’s perhaps another piece altogether. This is in some ways part of this small lectures series (the name I’ve settled on) and also maybe not, who’s to say just yet.

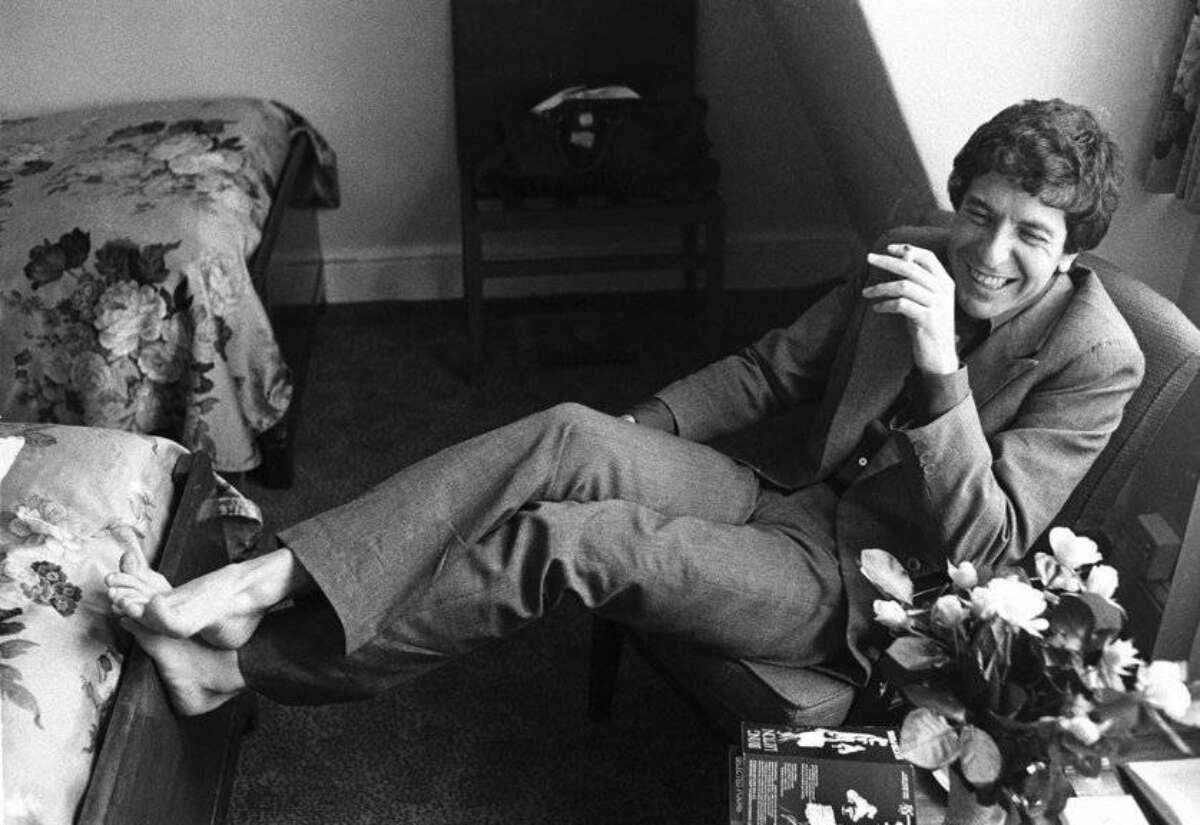

As I write this it is his birthday. He would have been 90 years old, and this old, old, dead man, was particular and peculiar in his effects on me as a 22 year old. It has been many years since I was introduced to him, and it’s hard to look back sometimes on all the ways I dug into and worked off if his work; tried to emulate something of him, pined after his lyricism and romanticism. The poetry I wrote at the time was prolific (in the plentiful sense, not the inventive) and embarrassing. I found constant and consistent treasures in this excavation. Something of that self deprecating charisma that oozed out of him; that he found some levels of success earlier, but it was his 30s where he came into the public consciousness with Songs of Leonard Cohen; the oddly tragic story of his initiation into music being a Spanish guitarist who showed him the guitar and committed suicide the next day; his desire towards constant levels of enlightenment without the enlightenment; his typewriter, and then his acoustic guitar, and then his Casio keyboard: his instruments of exploration; that requirement later in his life, after his agent had scammed him, to go back to touring—which he never liked—and then having it be a massive success drawing in new crowds and old; that he was someone who “could not sing” and yet did anyway; his place as a kind of holy fool in the public and in my mind; that in his face I found something of my face: the nose, the laugh lines, I’d like to think the kind eyes maybe; and that’s just what I can list off the top of my head as I think back to what I know about this man I never met and will never meet—unless, of course, there’s something to a truth of somewhere after this now that he seemed to dig into and not quite grab at. His is always a passing through, begging not to pass him by, a desire to think of those unthought. Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson’s jacket that reads “Leonard Cohen was right.” Father John Muir on Twitter once asked after seeing someone wearing a shirt of the slogan, what was Cohen right about? The answer many come up with is it referred to the back of Songs of Love and Hate, “They locked up a man who wanted to rule the world. The Fools. They locked up the wrong man.” Esoteric and vague enough. But that feels like the wrong question, coupled with a wrong answer, if only because its a shirt/jacket/slogan Cohen would never have taken upon himself. I can imagine his response would have been circuitous, a bit self-loathing, and slightly profound. But I love the line for the irony it gives to us.

What is there, if anything, to write about this man that probably has not been already? I certainly will not add much to a discourse, and for myself this is a self-serving piece I wished to write as I think back on what was on this day. I was reminded of it because my friend texted me Happy Leonard Cohen’s Birthday. It aligns with a day where I’ve been thinking of isolationist tendencies in myself and in him. It’s the mark of the artist to many, a moving back into oneself so as to come back out to others as if Moses carrying the ten commandments to the chosen people. This is a farce and never actually true, and I’d like to think the self-aggrandizing and undercutting metaphor would please Cohen.

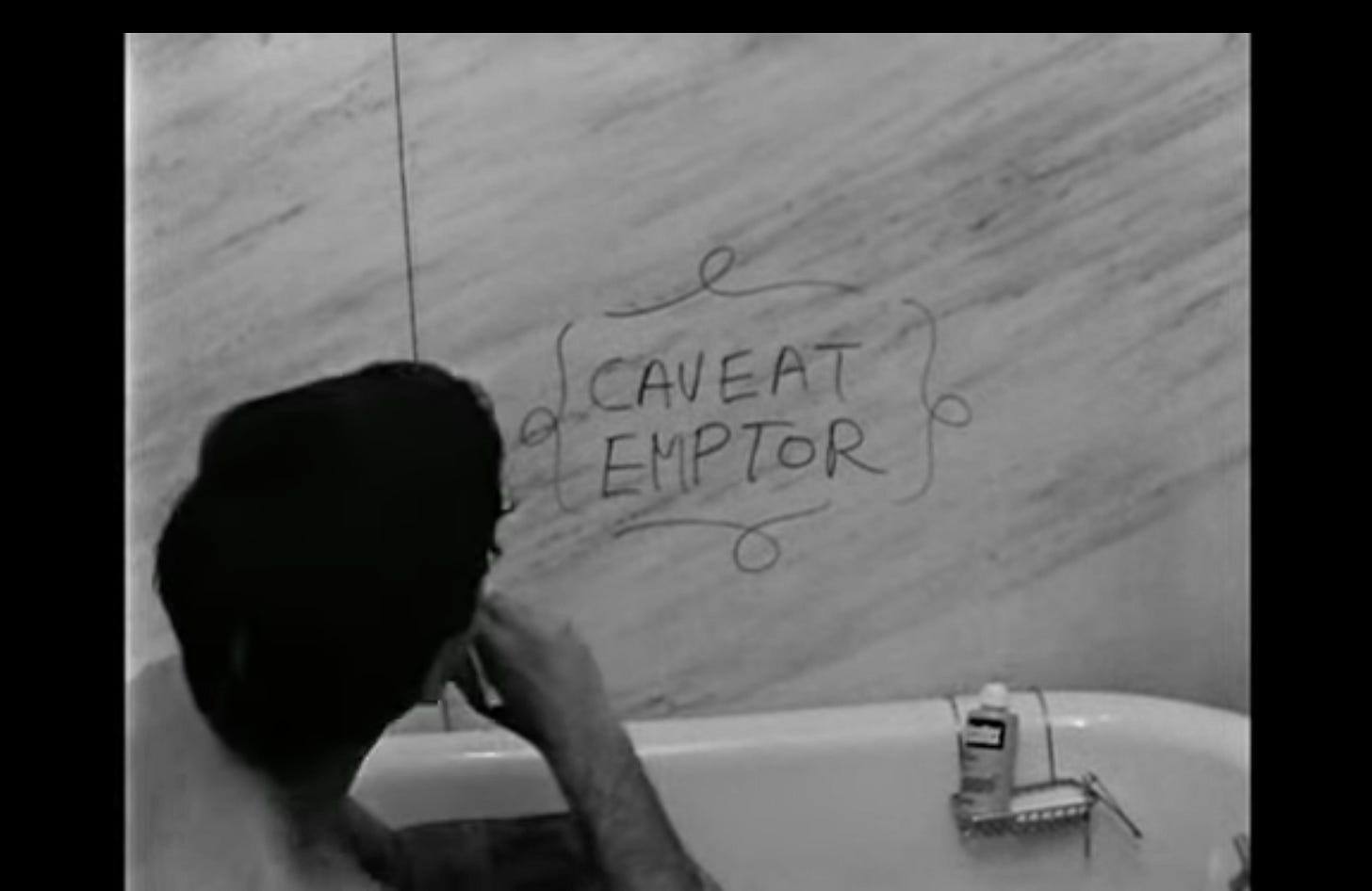

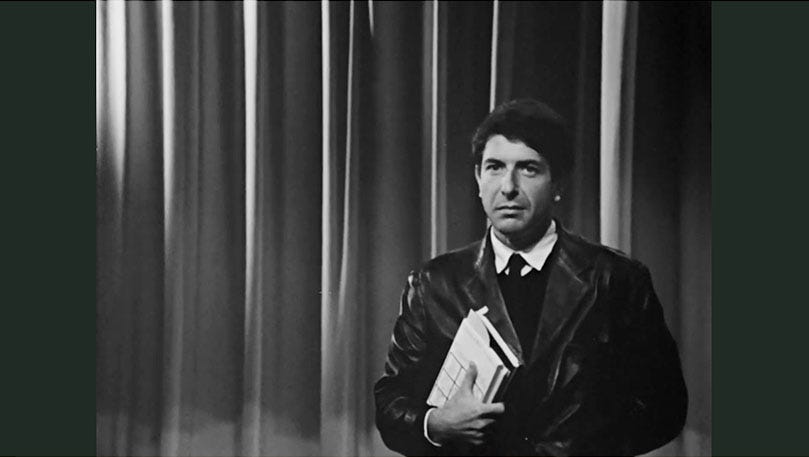

At the end of the film Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen, a documentary produced in 1965 by the National Film Board of Canada, Cohen was invited to view the footage, and in a very Cohen-esque move they filmed and presented it as an addendum. Cohen says at the end, “It’s a very privileged thing to be able to see yourself sleeping, I think it’s an experience very few people have. Of course, the fraud is that I’m not really sleeping.” The filmmaker responds, “It’s a very privileged thing being able to see yourself pretending to sleep.” To which Cohen muses, “Yes, yes I think that’s even more… that’s a privilege of a higher and more esoteric order because there are some people who are very very interested to know how they look when they’re pretending.” Not long after this a shot of Cohen trying to draw the blinds in his bedroom and failing comes on the screen and he’s quick to note, “I was always good with my hands.” Doubling both as a joke on himself, but also recognizing the deep irony of watching this film which will hold him in perpetuity. Following this is a shot of him in the bathroom to which he remarks, “Whatever the reason, a man has allowed a number of strangers into his bathroom. Now its true we’re making a film about my life and the film purports to examine my life closely and the bath is part of my life its still, regardless of the reason, here, 1964, a man has invited a group of strangers to observe him cleaning his body.” Filmmaker says you must find this interesting, and Cohen goes on. “I find it very interesting. I find it, I find it sinister. Of course I find it flattering, cause there’s a point where every man shares the Aga Khan’s delight at selling his bathwater to the faithful.” Self-consciousness towards the celebrity which would crop up around this display of himself as worth watching in even the most intimate of spaces, the most farcical of moments, the most like snake oil; and if I may say so is prescient, would he have said today “every man shares Belle Delphine’s delight at selling his bathwater to the horny.” Immediately he’s asked by the filmmaker what he meant by something he wrote on the bathroom wall in that scene, and if it was a message to the audience. He had written the phrase Caveat Emptor, “let the buyer beware.” And in classic Cohen fashion he justifies it, “I think that I had to for a moment act as a double agent for both the filmmakers and the public. I had to warn the public that… it’s like that little beep that goes through certain recorded phone messages that you hear on the radio. I thought I would make this little beep and let, let, let the man watching me know that this is not entirely devoid of the con.” A laugh, a pause. “I look much more like a man than I thought. In fact I think I’ve had a very, very mistaken conception of what style of man I was. The whole thing is changing now… I think I’m of a different style than I thought I was.” Filmmaker says that it may affect his whole life, to which Cohen responds, “I hope it affects my whole life.”

But why reproduce this nearly in full? Well when I speak it, I will speak Cohen through me, and there is a poeticism to this use of his meta commentary; it has become a tautology, nearly. But also I think there are levels of clarity in his words here that carry through much of his career. This notion of the con, the self-deprecation, the double agent, the dark humor. It is also a serendipity I want to revel in that I choose this birthday, this year, to think on this film and this moment in it. I’ve watched it many times through the years, but this is the year where I am the same age he was when it was recorded, 30. There is something in the “rightness” of it, that hand reaching back towards his hand reaching forward. Many wish to know what they look like when they are pretending.