An Aside for Fraser and Sandback

a selection from On Sentence Fragmentation: A Lecture in Parts

In July I read in Iowa City at Porchlight Literary Center thanks to an invitation from the phenomenal poet and publisher Margaret Yapp (you can find more of her work here and here). Following from that reading I’ve reworked the essay/lecture I read there which is forthcoming from the digital publishing side of Prompt Press. This piece is also working toward a larger book tentatively titled Frankenstein, or The Function of Reason (both titles of previously existed books mushed together). So in anticipation of all of Prompt Press I’m publishing this small selection from the essay lecture, and look out for more pieces incoming in preparation for that larger book. I hope you enjoy, and if you’d like to read the essay to which I’m referring you can find it here.

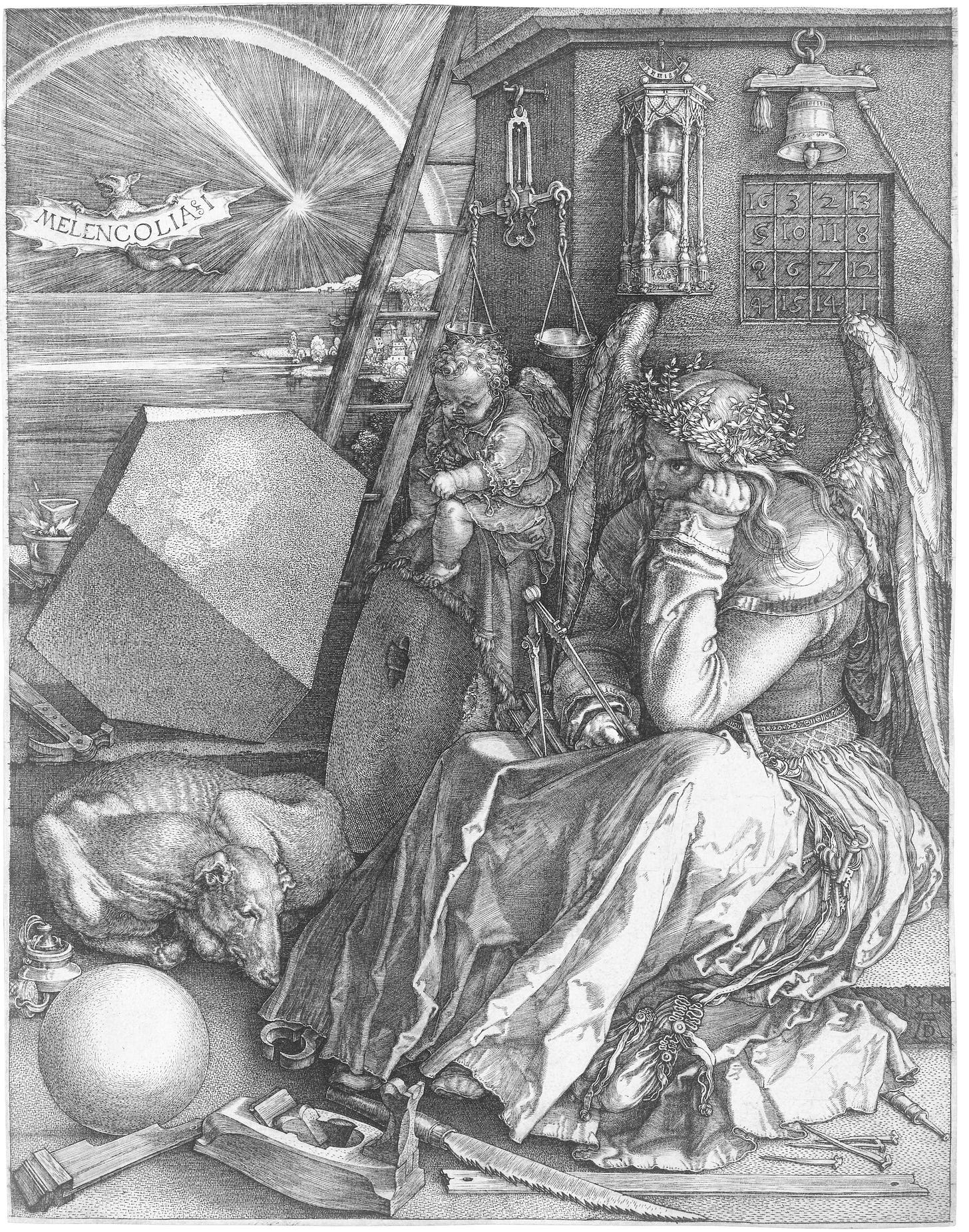

There is an essay by Andrea Fraser that each time I remember it exists comes to me as if a revelation, and—with the understanding of a possible hyperbole on my part here—I do mean it in the, not necessarily divine or supernatural sense, but nevertheless as something of a disclosure about something relating to human existence or the world. I am myself skeptical of art more and more each day, especially as it pertains to its financialization—and according to recent work being done by Fred Moten, Stefano Harney, and Zun Lee its securitization.1 And yet, I still find discussions around art, especially of a critical nature, to be worthwhile. The essay I’m speaking of is titled Why Does Fred Sandback’s Work Make Me Cry and funnily enough it speaks of him sparingly, or rather as sparingly and potently as his lines speak of the spaces they demarcate. These string sculpture demarcate space to be considered even as that space disappears. At its conception Fraser nearly put it on hold permanently. The title doubles as a note on the inciting incident which led to her thinking of the beginnings of the essay on a train ride home from the crying in question. But nearly simultaneously Fred Sandback committed suicide, and due to Fraser’s tangential relationship to the artist, felt it would be best to delay it indefinitely, Of course she didn’t thanks to the encouragement of Lynn Cooke. For this reason the essay is dedicated not to the man she did not know, but the work she did, which continues to live in all of its stark possibilities.

Fraser’s is a practice built out of institutional critique, a way of making art which challenges the core principles of its making. Art for her—and by extension herself as an artist—is an impossibility, and furthermore the violence that it enacts is what art is and does, namely:

There is a kind of violence against art and against culture that art is. It is there in the structure of art, in the structure of our field—just, perhaps, as aggression is there in the structure of our subjectivity. It is the violence of emptying the world of representation and function, communicative and material use, that is done when we insist on the primacy of form; it is the violence of separation we enact in all kinds of aesthetic distancing; it is the violence of splitting off shared culture and competence, cutting up shared language, that we perform in every narrowing dialogue with the history of our own field; it is the violence of the competitive struggles for differentiation, achievement, and recognition that so often drive our practices; and it is the violence of every intention to subvert, transgress, confront, challenge, critique, and negate.2

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to General Research to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.