On Collage

This post was written to begin to think through a future project in the works. I’m incredibly grateful to my friend who introduced me to Douglas Kearney’s book Optic Subwoof which brought me to the thinking that follows, and I’m grateful to Kearney for having shared the work, to have spoken something that now sits in writing.

If you want to support the work I do here, and the work I do in general, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It would be much appreciated.

It’s said that lightning struck to make it all happen. Something of an image fixed for a moment in time, moments of “angelic clarity,” “It seems to me that a person might be tempted to live by these moments too much; one might hold too hard to them, wanting to have scales forever falling from one’s eyes and lightning forever striking.”1 Frankenstein never actually used lightning to make his monster, his thing. It was some elemental essence of life, unspecified, unaccounted for in his recountenance of the events so as to prevent the “scales [from] forever falling” for anyone else I’d wager. That which he imbued into his creation, that collage of a creature. Or, really, the thing, the dæmon, the monster, the being he brought into life from many deaths, would more accurately be termed an assemblage, as it is many things, body parts, brought together to make a new whole. And so it is, but I say collage to bring in something else. A misnaming to introduce a word. That is a word that is useful because it lets me bring here a meandering through a thought Douglas Kearney performs in the middle of his lecture You Better Hush: Blacktracking a Visual Poetics. This is my own meandering inspired by his.

His began with a shower thought:

Humanity’s first encounter with collage was death.2

And it ends with two newer formulations, a movement of through from how, to what, to that and it necessarily brings back in the cut, the cut of collage, and the cut of sampling:

Humanity’s first encounter with collage was some disruption of their sense of place.

Humanity cut its first encounter with collage when it didn’t recognize how the disruption occurred.3

The final thing placed in the new context of the veldt’s nigh monochrome—what he was formulating as the backdrop of this first collage—was an uprooted bloom placed where it shouldn’t be, and known this way because it had been known. Decontexualization and recontextualization against this backdrop. There’s something to Kearney’s desire to think the thought experiment of this originary event, and necessarily disrupting any possibility for it to be so simple as an origin. “Lightning flashes are brief.”4

This thought here, of bringing in Kearney meandering on collage, is not to perform a decontextualizing cut however. He is interested in collage and ties it up with a relationship to the violent decontextualization and recontextualization, that is the (what he calls) the what had happened was, of the history of the African diaspora and the forced movement of these people by colonizers, slavers, Europeans. In beginning with Kearney’s collage, I find something of his relating it to matters of death—and then life, when its beginning formulation to death was unsatisfactory—as inspiring to how I’ve been thinking assemblage à la Frankenstein’s Monster as this thing relates to matters of life and death. This has been a thought of mine for months now, an idea of “autistic thingliness.” The desire for this collage of forms-of-thought stems from something Fred Moten wrote in regard to Erin Manning’s book The Minor Gesture, “All black life is neurodiverse life.” That is to say (as Manning understands what Moten meant) the baseline of being human has never been given over to black life. And so what is to be learned in the, what Manning would call, threshold between these schools of thought: black thought (which is to say following Moten thought) and neurodivergent thought. Collage and assemblage understand this crossing as always in a cut, to sample each other to bring in the context of that original making, the original never being the end, or as Ross Gay would put it, “we all know that nothing happens only when it happens.” Not to put other works to use, but to put ourselves in conversation with each other—something Gay elucidates in the acknowledgements section of his book the last quote comes from titled Be Holding: A Poem (see my previous piece On Be Holding).

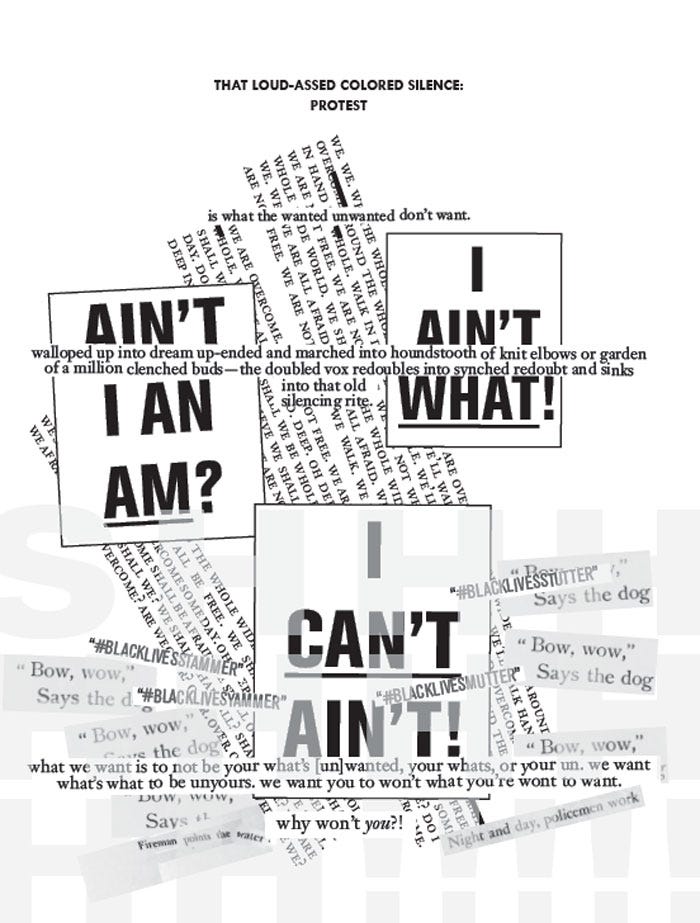

What’s so inviting to me about Kearney’s meandering here is that it comes from a place of iteration as thinking. Each form of what might be the ancestor’s first encounter with collage is no lesser, but simply a moment in a larger thought. Makes you stop like Kearney’s collage poems. Makes you hush, as he’d have it. Allowing this to be an iteration, to live in thought as something which will grow, preparation for elsewhere. I love Kearney’s lecture, as it is written down, because it does the work it’s asked to do in some respects, but on a larger level refuses it. When speaking of his collage poems that were meant to halt the viewer in their tracks, he speaks of how he eventually began to read them against his original desires. The unreadable poems. But the reading didn’t need to be the downfall of them, but rather a differing level of opacity, something which pushed against, in a different register, the desire to know proper. Poetry does that already, or rather, not good, but conscious, poetry I’d say does. What do we allow for in the knowing or not knowing, the silence of it all. But now I meander maybe a bit too far. I gotta come back to it, like Kearney says the ancestors tell him he needs to when talking collage.

I came to this because Kearney inspired something in me in regard to what I’ve been trying to work on. I felt the need to justify—or rather I felt the need to think properly through what one thing had to do with another: how does my project of life and death in regard to neurodiverse life in an assemblage, work next to, in conversation with, in silent concert with, Kearney’s thinking of life and death in regard to collage and its relationship to the decontextualization and recontextualization of the African Diaspora due to the transatlantic slave trade and its afterlives. Part of it simply has to do with the inextricable nature of the world with the world. To quote Erin Manning in an interview:

When I talk about neurotypicality I mean the systemic ease of crossing the threshold. This is what neurotypicality carries: a claim on the world. Neurotypicality in my work never refers to a person. Neurotypicality is the practising of an ease based on norms that underlie the valuation of existence. Neurotypicality claims space in very precise ways. It claims bodyings too. It moves without a stim. It speaks without an accent. It enters without a stir. It does these things not because there is actually a baseline human that fits into its category, but because it has trained us (those of us who pass) to create and recreate that baseline, and we are practised at inhabiting it – those of us who have access to its parameters. When Fred Moten says that black life is always neurodiverse life, this is what I understand: that blackness has never had access to this baseline. When Sylvia Wynter speaks of black life as excluded from the category of the human, this is also what I understand, that the human is the figure par excellence of neurotypicality, which is to say, Whiteness. Whiteness is not simply an epidermal configuration. Whiteness is the privilege not to have had to take the baseline into consideration. It is the privilege not to have had to think about how to pass. Whiteness is never to have had to make an effort at appearing in the know. Whiteness is crossing and re-crossing without ever noticing the threshold in the first place. Whiteness is the effortlessness of finding your place in existence. Whiteness is the assumption that the world is yours to inhabit and yours to define.5

A project to think through the potential inherent in an “autistic thingliness” will always (at its best) butt up against Whiteness, and it will need to reckon with its placement onto neurodivergence. That is, Whiteness’s attempt when it sees the proliferation of difference to flatten it out, and absorb it back in. The collage/assemblage of it all will allow the ability for difference to be its productive self. Difference’s capacity for multiple worlds existing at the same time. To think the thresholds that must be moved through, the openings collages onto each other. I hope for more to come, and am glad to have been able to be with Kearney if only by myself, and only for a moment.

Emily Ogden, “How to Catch a Minnow,” in On Not Knowing: How to Love and Other Essays (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2022), 6.

Douglas Kearney, “You Better Hush: Blacktracking a Visual Poetics,” in Optic Subwoof (Seattle and New York: Wave Books, 2022), 13.

Ibid, 20.

Emily Ogden, “How to Catch a Minnow,” in On Not Knowing: How to Love and Other Essays (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2022), 7.

Erin Manning, Halbe Kuipers “how the minor moves us: across thresholds, socialities, and techniques,” open!, February 20 2019, September 13 2024, https://onlineopen.org/how-the-minor-moves-us-across-thresholds-socialities-and-techniques.